My dog Scampy is one of the most affectionate personalities I’ve ever met, loving nothing more than playing fetch with his squeaky welly boot or snuggling in our bed in the morning. He’s also extremely reactive to strangers, to the point of perceived aggression. Found abandoned, tied up in a backyard in Romania, and then adopted into a UK home where there was suspected domestic abuse, it’s fair to say that Scampy’s life has been challenging. Initially docile, as he got to know us as his new family, Scampy became increasingly protective, lunging, growling and barking at strange humans and dogs. Would he bite a stranger if provoked? I don’t doubt it. Yet even when he wears his ‘Nervous Dog’ harness, people will still crouch down and approach him, shouting through the barks and growls “Don’t worry, dogs love me!”

Why don’t they take his warning signs seriously? Because Scampy is a small, cute, fluffy Shih Tzu-mix. He looks about as far away from a ‘dangerous dog’ as you can get.

That’s why I laughed out loud when I saw The Mirror’s recent ‘Time For Action on Dangerous Dogs’ campaign (it was laugh or cry). Last year marked the 30th anniversary of the Dangerous Dogs Act in the UK, a law that the two major UK veterinary bodies, the BVA and BSAVA, have long urged the government to scrap. Instead of this unnuanced Act which bans specific ‘dangerous’ dog breeds, vets want the UK to adopt an evidence-based ‘deed not breed’ approach to dog control law. This year, Battersea Dog’s Home, Blue Cross, Dogs Trust, The Kennel Club, RSPCA, Scottish SPCA and BVA all teamed up to push an #EndBSL campaign. Breed specific legislation (BSL) ‘sentences dogs to death’ because they look a certain way.

Section 1 of the Dangerous Dogs Act is just such breed-specific legislation, which bans the ownership of certain breed types perceived to pose a risk to public safety. These include the Pit Bull Terrier, Japanese Tosa, Dogo Argentino and Fila Brasileiro (unsurprisingly the Act does not ban the Shih Tzu).

Yet RSPCA #EndBSL campaign manager, Shelley Phillips, says, “There’s no robust scientific evidence to suggest that these types of dogs are more dangerous, more likely to use aggression or have a unique bite style that could cause more serious harm, than any other type of dog.” She’s right; the number of dog-biting and dog aggression incidents hasn’t fallen since the Act was introduced in 1991. In fact, NHS data shows that the number of hospital admissions due to dog-related injuries has increased. In the past decade, the number of admissions rose 30%.

Why? By designating some breeds ‘unsafe’, other breeds are therefore perceived to be unconditionally ‘safe’, encouraging lack of proper caution around so-called harmless dogs. Look at Scampy. Any dog can bite if provoked or mistreated, and such behaviour is both natural and arguably justified. Scampy’s aggression is a symptom of his fear of violent humans and his desire to protect myself and my husband from perceived threats. Should he be punished, let alone destroyed, for that? Of course not! The same applies for any dog, including those of breeds designated ‘dangerous’. The solution to dog aggression is not to blanket euthanise or muzzle certain breeds, but to understand why an individual dog might bite, based on their unique experience and personality, and work with the owner and dog to address the behavioural issue.

The Mirror’s campaign to add yet more breeds to Section 1 of the Act is therefore completely ill-advised, representing a step back for both public safety and the welfare of dogs who may be unlucky enough to be born a certain breed. Instead of blaming a dog’s breed for a bite, and by association the dog him or herself, the dog guardian needs to take responsibility for putting their animal in a position where they felt they had no choice but to defend themselves. The real problem here is lack of understanding of canine behaviour, ignorance of signs of distress, and lack of proper care. Scampy has never actually bitten anybody because he gives clear signals when he is upset and triggered: ears flattened back against his head, growling, lunging and barking. As he climbs this Ladder of Aggression (the series of gestures that a dog will give in response to an escalation of perceived stress and threat, from blinking and nose licking to overt aggression) it is my job as a responsible owner to remove him from the triggering situation.

As dog carers, we must ensure our animals are humanely trained and, if known to be reactive, kept away from situations where they may be provoked. This is true whether your dog be a Pittie or a Poodle. In a situation with an infant, even a bite from a Chihuahua can be fatal (as The Mirror acknowledge with the line “Animals seized range from a tiny Chihuahua to American XL bulldogs”!)

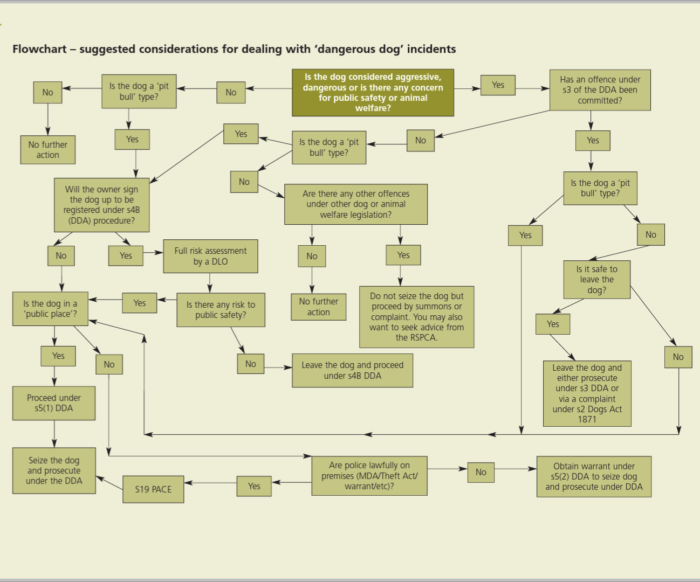

More obviously, there are clearly negative welfare impacts on dogs who might be suspected of being a prohibited breed type. Defra’s ‘Dangerous Dogs Law: Guidance for Enforcers’ document states that “Prosecutions can be brought before a Court based on just the physical characteristics of the dog (i.e. what it looks like).” The prosecutors don’t need to prove that the dog is a ‘dangerous breed’; instead it falls on the owner to “prove to the Court that the dog is not of the prohibited type… If a police officer alleges that a dog is a PBT type then it is assumed to be such a dog until the defence proves otherwise.” As you can see from this algorithm, a dog that looks like a banned breed can be seized even if it is not considered aggressive or dangerous, and even if there is no concern for public safety or animal welfare.

Under the Act, harmless dogs can thus be seized, removed from their loving family homes and euthanised. Best case scenario, the owner can fight to have them exempted through the courts but, if approved, they must adhere to a strict set of rules such as always keeping them on lead and muzzled when in public. At a time when shelters are overflowing with dogs whose owners can no longer afford to care for them, proposing a law that will forcibly remove happy, cared-for dogs from their homes seems the height of madness. One ex-shelter worker in the UK explained to me how distressing this situation can be, for everybody involved:

I worked at two rehoming centres in England and, during that time, dogs would sometimes come in who were suspected to be ‘of type’ and had to be seen by the police/local authority to confirm if they were a banned/’dangerous’ breed. A specialist police officer would usually come out to the rehoming centre and take various measurements and observations of the dog/dogs in question and make their decision from there. This would happen at least once or twice a month. I remember there was a litter of puppies who came in with their mum, who was a Staffordshire Bull Terrier cross. The breed of the father was unknown and there was some suspicion that the puppies were ‘of type’. A police officer saw the puppies and deemed them to be a ‘dangerous’ breed and they all had to be euthanised. It was absolutely heart-breaking. These puppies had never hurt anyone, were totally innocent, and were killed because they ticked a number of boxes on a list of ‘characteristics’ that meant they were considered dangerous in the eyes of the law. I remember the police officer being really upset about it too – the legislation is not fit for purpose.

Rehoming centres that take in strays or other dogs given to them are not legally allowed to rehome dogs that are on the list of banned breeds, so if there is any suggestion that a dog may be ‘of type’, they need to be checked (otherwise the dog could be rehomed and then the new owner may have to deal with the issue later on). Witnessing perfectly healthy, well-behaved dogs be put to sleep because of this law really impacted my mental health. Even though I worked in rehoming centres over 8 years ago, I often get upset now thinking about those dogs who were killed for how they looked.

Working with Scampy to address his fear and reactivity has made me a better dog guardian, as well as a more responsible member of the public when interacting with other people’s dogs. I no longer approach a new dog off the bat, instead allowing them to come to me if they want contact. And my bond with Scampy is so much stronger because of our positive reinforcement training sessions. Progress is slow, but it’s there: perhaps one day he will be able to be off the lead on busier walks, his high-vis warning harness consigned to the cupboard. Thankfully, because he isn’t a ‘dangerous breed’, we will get that chance. Unlike the unlucky dogs described above, Scampy’s future isn’t under threat.

Instead of advocating for an extension of a law that has no evidence of success, and has caused only devastation and heartbreak, The Mirror would do better to push for additional research into dog aggression, helping us better understand our dogs, and educational programmes to promote responsible ownership and improved public understanding. But I guess that wouldn’t make for such a sensationalist story…

Thank you so much for the information you posted. Having owned Staffordshire Bull Terriers for over 30 yrs I couldn’t agree more with you. All dogs bite, especially small ones.